South Stream Swims Against the Current

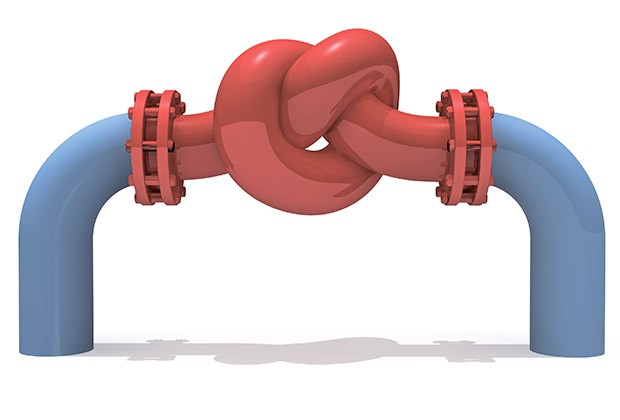

The South Stream project is a very topical issue, as it determines Europe′s prospects for energy security. Not so long ago, the project was subjected to considerable criticism from the heads of some European countries, largely due to the political crisis in Ukraine and the role that Russia plays in it. WEJ tried to find out how the South Stream project impacts Europe and the reason why certain European leaders wish that it would fail.

The main idea behind South Stream is very simple: Deliver Russian gas to European consumers without intermediaries, and especially bypass Ukraine. In 2005-2006 and in 2008-2009, Russia was in a state of so-called “gas war” with Ukraine due to a disagreement between the Russian supplier Gazprom and the Ukrainian Naftogaz. Russia twice cut off gas supplies to Ukraine, and due to this Europeans failed to receive gas that they had already purchased. In fact, both Moscow and Europe agreed that the unsanctioned siphoning of gas and the probability of failure due to the political changes in Ukraine define the need for an alternative route for delivering fuel.

Of course, European politicians would be happy to find an alternative source to Russia for its gas deliveries, in order to reduce its dependence on Ukraine for transit and to reduce Europe′s general dependence on Russia as the main energy supplier. This is why Europeans were actively developing the Nabucco-West pipeline, which was proposed to run from Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan through the countries of the Caucasus and Turkey as a way of bypassing Russia. However, the project was abandoned in 2013 due to its expense. Of course, in addition to its purely financial difficulties, Nabucco-West could not withstand competition and pressure from South Stream.

The South Stream project, which in addition to Russia (represented by Gazprom with a 50% share) involves Italy (Eni with 20%), France (EDFGroup with 15%), and Germany (Wintershall AG with 15%), has been discussed since 2007. In 2012 the member countries of the project began work on the construction of the Russian part of the pipeline. Currently, the possibility of altering the sea portion of the route is being ascertained in light of the annexation of Crimea, the use of whose territory could minimize the distance. In the meantime, South Stream would have to be built along the bottom of the Black Sea to the Bulgarian port of Varna, and then it would split in two directions: one to the northwest and the other to the southwest. To date, a number of intergovernmental agreements have been concluded approving the construction of sections of South Steam with Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Greece, Slovenia, Austria, Croatia, and Macedonia. In fact, all the technical problems have been addressed, and the project can go ahead according to schedule. In particular, in 2015 work on the first branch should begin, and in 2018 South Stream should be fully launched.

The volume of gas to be delivered along the 2446-kilometer pipeline is expected to be 63 billion cubic meters by the completion of construction. Experts estimate that by 2020 it may reach 80 billion cubic meters, and by 2030 it could exceed 140 billion cubic meters.

What, exactly, is the problem with the project? According to Tim Boersma, Fellow, Energy Security Initiative, The Brookings Institution, “For Russian citizens there is a reason to oppose, as I have seen little evidence so far suggesting that this pipeline can be profitable. From a European perspective, if markets in Central and Eastern Europe do not make efforts to further integrate their markets, South Stream may, as a result, reinforce Gazprom′s dominance in that part of the continent, with potential market abuse as a consequence.” Indeed, the assessments by experts regarding the cost and profitability of the project vary in their degree of optimism. According to the most conservative estimates, Russia needs $16 billion to build the pipeline network, an amount that will certainly prove difficult to raise now. On the other hand, concerns about the possible abuse of the market by Gazprom in the future are not so simple. At least this is how Geert Greving, Chairman, International Gas Union, and Nonresidential Senior Fellow, Energy Security Initiative, Brookings Institution, sees the situation: “The more pipelines the better and the better the internal natural gas market is going to function. Pipelines are all regulated in Europe, so opposing the line towards Europe is quite amazing and strange.”

Text: Anton Barbashin

Comments are closed.